A Definition of Value in Urban Design

Alain J. F. Chiaradia

Faculty of Architecture, Department of Urban Planning and Design, The University of Hong Kong

“There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says ‘Morning, boys. How’s the water?’ And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, ‘What the hell is water?’” said David Foster Wallace. This is Water, (2009).

The clueless young fish are not, as one might suspect, our students. Instead, they are all of us e urban design practitioners who deploy ‘value’ instrumentally day in day out and are immersed in it within every decision we make. Yet we do not sufficiently reflect on what value in urban design actually means, and what the implications of deploying value arguments are. This paper is about what the hell value is.

The process of scaffolding our students’ learning and the insights that they have thrown back at us allow us to address the objectives for this paper. Firstly, to (re)define what value could be in urban design; that is, to develop a definition of value that is relevant to urban design. Secondly, to derive a corresponding definition of ‘urban design’ itself, in terms of value. This Section discusses the former, an ‘urban-design-relevant’ definition of value.

The Development Appraisal is an urban design-sensitive value appraisal. It seeks to bring into explicit consideration the questions of ‘to whom value accrues’ whether private and public, ‘what the function of value is’, ‘whether it is value in exchange or in use that is being considered’, ‘the different aspects of urban design’, and ‘identification of sources of value from amongst possible urban design features’.

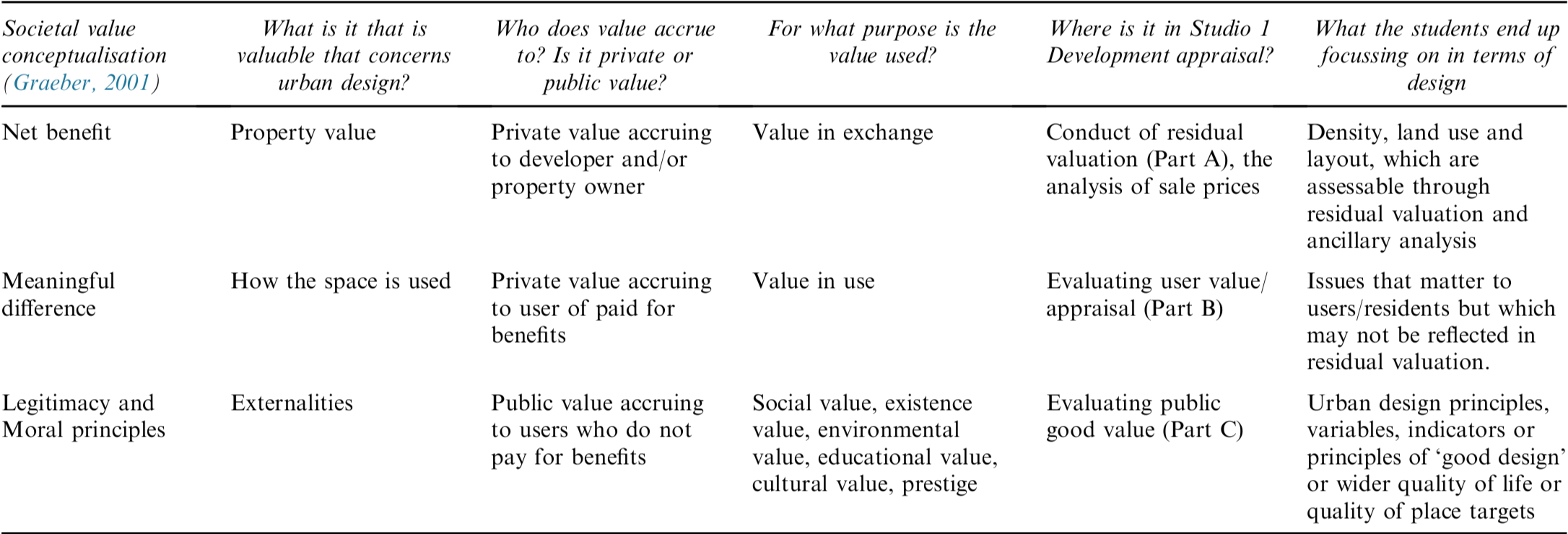

In fact, the three Parts, A, B and C of the Development Appraisal were structured around the trio of concepts of societal value (Graeber, 2001) discussed in Section 1.5. These three value concepts underpin the types of values created/destroyed by doing urban design (see Table 2) and are therefore value concepts that designers should be conversant with if they are to deploy them.

In the first column from the left, the three concepts of value e net benefit, meaningful difference, moral principles recategorise the aspects of societal value with which urban design may have any conceptual interaction with.

The second column describes the manifestation of this type of value in urban design practice and sets out those values that urban design activity typically affects, and with which urban designers need therefore to be concerned. One could consider whether these values are associated with tangible and intangible urban design outputs, or the processes of designing.

The third column maps who these types of values typically accrue to, and whether this can constitute private value, or public value (Kelly et al., 2001; Moore, 1995; Talbot, 2008). This is a fundamental issue because arguably, there can be no value without someone to which that value would be valuable; knowing who the beneficiaries are helps us understand the equity of a given value configuration.

The fourth column identifies those instances when the urban design-specific value concepts might be useful. These are classified according to common concepts in public economics, primarily around the question of whether it is value in exchange, value in use, or more exotic types such as non-use value or existence value (CABE, 2006).

The fifth column simply states where in the Studio 1 processes this value is in play, respectively, Parts A, B and C. As already discussed, in Part A, we introduced students to the idea of value in exchange via ‘developer’s value’. In Parts B (added value of urban design) and C (public good), students were asked to make explicit in monetary terms, values which usually remain un- articulated (Biddulph, 2007).

The sixth column is about what, as a result of having considered this value in the valuation exercise, the student ends up focusing on in their design.

This table demonstrates how value can be used as a central instrumental concept to help ensure site-specific urban design responses. A ‘value’ approach starts with who the stakeholders are, what value and what forms of value accrue to them, how do they apprehend that value, and what do they do with valuable assets, and stakeholders are always site-specific. Thus, the three definitions of value in the first column and top row headings are general questions applicable anywhere, but the table content in Columns 2, 3 and 4 would be context-specific. The urban designer needs to know about the system that governs the rights to benefit from different aspects of the development, and therefore the type of stakeholders and the nature of their interest in those benefits, about its property development processes and how value transfers between stakeholders in such a system, and the role of physical configuration in this system.

The highly coherent and plausible multi-way triangulation between the different manifestations of value, stakeholders and purposes of value, based on non-urban design-specific literature (Graeber, 2001), urban design specific literature (British Council for Offices, 2006; CABE, 2006), the authors’ own investigations into values in the Barbican sub-market that underpinned the Valuation Handbook and the pedagogic design of the Studio, and the reflection on student work and student experience gives us confidence that this framework is robust.

For urban designers and valuers chugging along in the middle-range concept of ‘value as net benefit’, the links to the higher level concepts of ‘value as meaningful difference’ and ‘value as moral principles’ should inform everyday practice. Given that urban design is often dependent on property development, given its status as a ‘public art’ (Marshall, 2015), its influence over social goods and its political nature, all three conceptualisations of value are important, at the same time, for a concept of value in urban design. For an urban designer, all three notions of value should remain in play and underpin urban design practice, not just the easy-to-measure ‘value as net benefit’. A designer should always be at least aware, if not in control of value as an instrument, and not the other way around.

Table 1. Three conceptualisations of value in society and in urban design

(文章来源:DESIGN STUDIES VOL.49 NO.C excerpts)